What was the inspiration behind The Book of Moon? There were quite a lot of influences from my childhood on the structure of the world the story is set in. I had been asked by friends and acquaintances for years to write about my childhood because there were just a lot of things going on and I come from a big family and there’s all the stuff that goes with that and as a story they thought it would have been a good read I guess. But I felt that people reading it who didn’t know the context of events would be needlessly judgmental towards those who were involved in my upbringing because only I have all the facts about that as they pertain to me, and I feel it’s my right and my right alone to judge what’s happened to me, so I decided not to do anything like a non-fiction memoir. Now, I had always written stories to cope with the world around me even from early childhood and I had come up with these dog-like characters in elementary school so that was sort of a running thing for me. When I wrote Look Left, Walk Green, that was a book about a singular thing that happened to me as an adult and was geared towards helping others understand and get through the same thing. It was around the time I was writing that first book that I realized that the short stories I’d done of the dog-characters as a kid were really representative of things in my life and I’d never really caught on to that as I was writing them. Now there are many ways of telling a story about oneself- you can tell your life’s story as the child of someone or the parent of someone, as someone’s employee or employer, someone’s sibling, a man or a woman or a person of a particular race or religion… all these are valid representations. I chose to write a story about my life as a child and adolescent with a mental illness and the family I have through the psychiatric system and I chose to do it through the dog-characters because it was into their world that I’d go mentally to deal with being a kid but later also a psychiatric patient. So it made sense to write the story in that manner and once I made up my mind to do that, it came together cohesively as one volume instead of being a collection of smaller bits here and there.

Why dogs? Honestly, I just really liked dogs as a kid. I got my first dog when I was 6 and began drawing “dog-people” (my friends always refer to them as that, haha) around age 7. I was alone a lot after school and hung out with my dog, so I guess one thing led to another. Originally, they had longer noses and some wore sort of Pierrot-style clothing but as I kind of refined them over the years I noticed they were getting chubbier in the face. Now some artists do intentionally give their characters “like” characteristics; I don’t recall making that decision, but I think they did sort of start to look like me as a kid. I had round chubby cheeks and sort of angled eyes when I was small. Later for the purpose of being able to draw more expressions on them, I had to round out the eyes a little more and narrow the noses to be able to show the difference between younger and older characters.

The Book of Moon is a fantasy story with fictional characters. Which parts, if any, are literally about you? Well, the story as a whole is. It’s me dissecting myself at different ages into separate characters so most of them have characteristics of me OR certain people who helped me through mental health treatment. Of course, in a fictional story you have to add details or instances that are “made-up” to move the story along. I didn’t literally ever live in a palace of course, but I stayed with people who had houses that were like palaces to me. I didn’t grow up in a war-torn area but I did grow up at the end of the Cold War and there were 4 divorces in my immediate family before I was out of high school so it often felt like the grown-ups were in the middle of a war. I wasn’t dragged across a land of famine, but I was sent far away to live with relatives I didn’t know. There were times when my life changed extremely fast and I had to get used to totally different people and circumstances with no warning. I had no say in or control over these things and I felt a lot of betrayal. So, there’s a lot of details that are changed but much of the inner thoughts of the various characters are things I thought at the time as a child and adolescent about what was going on around me such as the constant interruption of hospitalizations during school and this terrible tension between my family, myself and the psychiatric system.

Have you written any people you know into the story? Not family as in biological or step or adopted family at all. This is a story that includes psychiatric family and even then, they’re mostly not major characters. I tend to write in a lot of unrelated details from people around me that are just one-offs. For example there’s a line in a sad part of the story where feathers are spilling out of a hat as if the, joy of their ideas or essence were spilling out and that was actually about a boss of mine who wore her hair out one day and I thought it was so beautiful it was as if joy had leapt right up out of her head. Little bits like that. F’ala’s purple dress she wears all the time was based on someone I was in treatment under for a short time who wore a lot of purple. The little child that favours F’ala when she’s a servant is based on another clinician I knew much later in the same office and was always very supportive of my artwork; the line about her laugh specifically. I would say there’s really only one main character I patterned off of a real person and even then, it was the essence of the person, not really specifics.

You’ve said you think teens can relate to this story. How exactly? When I was a child and teen there was a lot of loneliness and people missing in my life and that was before social media. In fact, the internet was just coming into the commercial arena so few people had an internet connection until I was in college and even then it wasn’t used like it is today. As a kid I read books as if I were starving, always taking piles of them everywhere. I made friends in books and later on, in user groups on the internet and that was what kept me going in-between these really disruptive spurts in my life. Today we complain kids seem so different than in our generation and I think it’s mainly because the tech they use and are exposed to is so different and evolves so fast that they can communicate in ways we never could before. But what I see online and hear from kids I’ve talked to is the same: kids are still looking for meaningful relationships, they want to be included and accepted for who they are and above that, they’re struggling to figure out who they are and often times they feel isolated. Some groups more than others, some kids just don’t connect well. Many feel like it’s a war between themselves and their parents and that’s completely how I perceived the world when I was that age.

I think many will completely understand how Mi’hal’ē longs for a world that rejects her, how seemingly simple stereotypes and beliefs can spiral out of control and become destructive. I think they can also relate to Ā’dō who just wants to be “normal” in her view yet also wants to have a decent relationship with her sister and on the other hand, with F’ala who is in love but at the same time feels like the secret she carries makes her worthless of deserving love. Because we all struggle with “secrets” of one kind or another. And I think, because I perceive that the kids growing up now are also full of good intentions and huge dreams and the true desire to make change in the world for the better, that they’ll understand how Mi’hal’ē comes to make her choices near the end of the story. For those who don’t find it terribly hard to fit in and make friends and get on, perhaps they can find some understanding of those around them who do. Of course sadly, there are also the kids who go through terrible things very young and are unable to speak out or if they do, experience stigma in this world that tends to blame victims right off the bat and I hope that they can also find something to identify with in this book because there’s a thread of that as well.

There are a lot of themes running throughout the book. Can you speak to those? Yeah, there are a lot and I wasn’t consciously plotting it out like that as I wrote but noticed them after. I think there are three main ones that sort of kept striking me during editing: 1. How we maintain our own identities 2. How we define family and 3. The influence love has on our choices. So, Mi’hal’ē isn’t sure of who she is and when she figures this out, she has to somehow reconcile that with who she’s believed she is all her life. And we sort of all go through a version of that in adulthood because we’ve lived as our parents’ children and then suddenly we go into the world and we have to figure out who we are as all these other things- employees and college students and boyfriends or girlfriends and later spouses and parents and whatever else comes along. The world is suddenly seeing us as something other than how we see ourselves and has different expectations. And adolescence is a really important time where a ton of work is going on to move into those identities so there’s a fair amount of stopping and starting and serious choices to be made. And then there are situations where we get out and figure out there are some fundamental things we thought about the world aren’t true or are no longer true and then we have to figure out who we are in relation to our beliefs or faith. So, it’s a big theme because it’s important stuff.

Then there’s how we define family. Some of us come from a nuclear family that’s well defined and everyone is secure in who they are to each other. Some come from really dysfunctional families where there’s abuse and unrest. Some have their family redefined by divorce or death or by taking in new family and their roles are sort of slippery. People who have been adopted or conceived by other methods have to figure out personally how they “see” the different parts of their family, if at all. Some have been utterly rejected by family and make families of friends or communities. And all of these are valid families, but we have to also figure out “family identity” at some point as we move through life, and again, big important stuff.

But I think the most important theme is of love and how that feeds into the choices we make and the lives we lead. Because we can have these lonely, disconnected, disjointed lives and yet if there’s just one loving connection to another person, we can overcome our circumstances and go on to be more productive and happy than we ever imagined. It’s really easy to think oh, what can just one person do? Like, I wonder how many changes for good never happen because we get stuck in that lie? Yet so many people who overcame dire circumstances and influenced the world throughout history could name a single person who was so influential to them that they had the strength to become who the world would remember them as. We can do enourmous things on the strength of the love of just one person and that’s the main theme arc that carries though the whole story.

You mentioned that Mi’hal’ē has to make some really important choices. Can you speak to how that related to your life when you were writing The Book of Moon if it did at all? Mi’hal’ē is sort of a saviour-type character within the story and she has to make some serious choices without knowing the outcome. For me, the situation was very different and was much later in my life. Again, back to mental health and how it played out for me, I was hospitalized at the end of the asylum era so right after patients were released from the long-term asylums in an effort to move them back out into the community. But that took a while to work out and mental health itself is still going through major reforms little by little now. When I first entered in my early teens it was a very punitive system. There was no focus on getting better, you were told you would never get better, you were a problem to society and it was more or less commit, medicate and then toss you back out until you had trouble and got committed all over again.

Over the years I saw a lot of abusive stuff before patients had advocates and such that they may today and I, like many patients at that time and of course in the decades before, saw mental health staff as the absolute enemy. The stigma and discrimination in the outside world sort of made sense then. People were afraid of “crazy” people and it made sense that they would be coming from the stereotypes that society had at the time and still struggles with. But for hospital staff to also act in that same way was really upsetting because it meant to you that there was no help anywhere on the outside or the inside. You were either rejected in your everyday life or caged up until your insurance ran out. But as time went on and there were movements to reform and revamp how psychiatry treats and sees patients, I was able to separate the former staff from the newer staff in my mind and for the sake of those few who were good to me and I consider absolute family now. And I suppose, ultimately, you could say that the way this story ends is a sort of love-letter to those in the psychiatric system from therapists to nurses to even those who, over the years took buckets of my blood for all sorts of tests, because they each had a direct hand in proving to me that people are not all untrustworthy or abusive or apathetic. Because when I met these people in my early teens, that’s absolutely what the world looked like to me. So if I ever have the privilege of doing anything good for humanity, those people can definitely be sure they had a hand in that. That’s not to say my family has nothing to do with who I am; they do, but I would say those people that stuck with me in the psychiatric system have had the most direct influence on who I am today.

You’ve said this story is based on your experiences growing up with mental illness. Why then did you make the decision to have Mi’hal’ē ‘s difference be skin colour? I did that deliberately because I’m aware that we’re still in early days of mental health education and the popular view of mental health is that it’s equal to mental illness and this isn’t so- mental health is part of everyone’s “total health” and must be attended to in order to be a healthy individual. Mental illness is when something goes wrong with mental health so it’s still hard for people to envision this and the stereotypes of a person with mental illness being a disheveled homeless person who talks to themselves and shouts on the street are still really hard to break away from. Mental illness is under the “invisible” disabilities that you can’t just eyeball a person up and know that’s what’s going on. So, I knew just writing the character as being different because she might have Bipolar Disorder or Trichotillomania, etc, was only going to connect with a certain group of people already familiar with those disorders. But, unfortunately, we as Americans are extremely attuned to appearance and we all notice immediately if there is something different about that. We’ve made an artform of discrimination towards skin colour and weight/ body shape and adolescents are really the ones to suffer for this because they’re already going through mental/physical/emotional changes at this point in life and it’s hard enough to deal with the normal stuff because you’re so much more aware of those stereotypes at that age.

So, I knew colour was going to be relatable and I wanted to meld that somehow with the mental illness so in the story Mi’hal’ē is mistaken for the harbinger of death and she’s in danger because of that and separated from society. One big thing about persons with mental illness is that separation from society is often huge in their lives and the perception that they are dangerous by the public is always there, as you can see from headlines about mass shootings and the constant commentary online perpetuating that stereotype. For persons of colour there’s no escaping long-held stereotypes because they can’t just hide or step out of their skin. And I was interested in the folk beliefs around the world around persons of colour with albinism and how that effects their sense of self and others’ perception of their cultural authenticity when the defining skin colour is absent. So those were all ideas sort of vying to be included in that decision. I felt that the practice of reducing a person’s identity to something as simple as a colour was a good metaphor for the practice of reducing a person’s identity to a diagnosis. It’s not the same experience but the idea behind it is the same and I hope relatable, because even if readers don’t all have that same real-life experience, they’re still likely to be aware of it going on in their world. As Mi’hal’ē notices several times, she is told (as children are told), that uniqueness is prized and we should strive to be ourselves but when she steps outside the door she knows that this isn’t the truth in practice. And as a person who grew up with an eating disorder I was all too aware that “being yourself” was just fine as long as it stayed within acceptable visual/ weight limits. I always found myself outside of them no matter how hard I tried. And I want to note that in Ebūda there are a lot of things we grapple with or have in human history and they’re in the story because again, this is a story representative of my life and those were things that were present in the world around me. It’s not meant to condone those things. I just don’t think that children/teens/young adults are stupid or ignorant of the terrible things of the world. I don’t think they ever were, but in a modern age always connected to the internet, they’re moreso aware than ever.

You have one character with a lesbian orientation and one who is a transgendered female. What went into the decision to write them as such? Well, when you are writing characters for a long time (and I had known many of these characters for over 20 years by the time I finished the manuscript) you get to know them fairly well and they become their own beings you like to talk to in your own thoughts. F’ala was always tough; getting her to speak wasn’t easy. I had to initially make up a lot of details with her because she wouldn’t give anything away and early on, she didn’t have much to do with the overall story. She was more or less a means to get Mi’hal’ē to the next part of the book. One thing that bothered me and I could never get right no matter how many times I revised it was the reason F’ala agrees to take care of Mi’hal’ē to begin with. F’ala is a stubborn girl and it wasn’t until I had had a few really negative things happen in my own life and had some time to think about what was going on with me by myself that she just came out with it and I realized she was gay. Boy, I was so relieved because I understood then that the story is as much hers as it is Mi’hal’ē ‘s and it was pretty easy then to go back and sort things out. The hardest bit with F’ala was not allowing the writing to be too sappy or trite- I wanted it to be as faithful to her as possible because without F’ala, Mi’hal’ē can’t do anything. She literally cannot be who she is without F’ala. And F’ala is capable of great, great love so there’s a story there. We’re not talking about a crush, we’re talking epic, self-sacrificing stuff you wouldn’t think of this sarcastic character. So that wasn’t really a decision I think, it was an ah-hah! moment I’m so glad I had and I love her very much and will never change her in that regard.

As for Úā’la, she doesn’t have but a tiny part in the story (that was once a short chapter of her own and cut for length’s sake) but it’s a very important one and she’s a very strong character. Now the thinking behind that was that I was really struck in my college years by the portrayal of transgendered females in Japanese anime. So you’d have this sort of campy, pretty lady everyone knew was male and they provided all this comic relief but then somewhere in the story when it really counted, when something really critical was going on, that campy comic relief character would come to the rescue and make the supreme sacrifice to save the main character or outdo the traditional male characters in valour. And it was like, they were concealing this great bravery and strength underneath that stereotypical facade. That sort of juxtaposition of what we think of as traditional male and female attributes all together in one character really impressed me. This was a depth to this sort of character I’d never seen in Western film. The stuff I grew up watching almost always had one girl in the bunch and the boys were always either in love with her or saving her, so anime gave me some other types of characters to chew on and that particular type felt right for this character. We now have women superheroes who display the “male” traits of strength and courage but that wasn’t even a thought for me when I was a kid so again, that mixture of both types of behaviour and traits was a game-changer for me all-around. Now Úā’la doesn’t have that comedic side, and the way I wrote her states that she has both male and female characteristics so that may be mistaken for gender-fluid. But in my mind she is male identifying as female and displaying traits of both, again as a nod to that portrayal in anime.

There’s also the business of Lān stating he was a female in the life before, as a star, and this has little to do with gender-swapping and more to do with the curses of the Guardians to not be readily recognizable to each other. Because those curses are so individual, some Guardians can recognize each other, some can’t.

As you’ve mentioned, the Book of Moon is a metaphor for a childhood living with mental illness. How do you manage that now that you’re an adult? I have Bipolar Disorder II and Eating Disorder NOS (Not Otherwise Specified) so those are conditions I have to take care of every day. I take medication daily as well as take regular exercise. I go to therapy and a skills group for regulating emotions/ cognitive functions. Otherwise, I attend church, try to keep a decent sleep schedule (it’s so hard!!) and I connect all the time with others online who also live with mental illness. I work full time, write and draw and like to garden and hang out with my animals and my pretty cool husband. I feel like I have a pretty normal (if busy!) life! And you can almost always find me with my music on. It just helps me manage.

Mi’hal’ē says that she is given something better than love; acceptance. I thought those were the same thing? To me, they’re not. They’re like best friends but friends can be really different. So, what comes to mind is like, when someone says to you, I love you, but. And teens can all relate to this and at that time in your life, a lot of that is developmentally normal. Your parents love you but… if you could just eat better, get to school on time, get to bed on time, return the car keys, etc. they’d like you a whole lot better. And that’s ok because your parents are responsible for teaching you adult skills. So, they do love you AND you also need to shape up a little. What I’m talking about with Mi’hal’ē is when someone tells you they love you but they’re not comfortable with who you are so they don’t like you so much and we often think automatically, then they don’t love me. If they loved me, I’d be free to do as I wish and they’d still love me. So, this is love with conditions. It’s a fine line. Sometimes people just need to get to know us better or let go of their limitations. Sometimes we need to bend a little or help them understand us. Sometimes one or both of us actually needs to change and we throw that love card in to justify not doing it. Because nobody actually owes us acceptance. When we accept ourselves we gain this confidence and that’s like a magnet for other people and it helps them to then offer acceptance to us. I think you can love and still be pretty rusty with acceptance because we all show love differently. For some, acceptance is an automatic part of their way of loving; with others it’s something that has to be earned from them. And when we’re talking about parents and children, parents sort of automatically love children but as they get older there’s lot of things they have trouble with or don’t accept about them. Acceptance is more a cognitive choice. So, Mi’hal’ē is musing that someone in her life who was more an “earn-it” type of personality made that difficult choice to accept her and for her it’s worth so much more. It’s the thing that makes her feel loved.

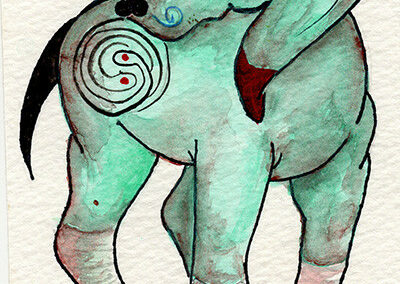

Let’s talk about the art for a second. You did all your own artwork for the book. Can you tell us a bit about your process? Well, I had been drawing these characters for so long, I had boxes of art gathering dust and when I always sat down to do an actual book I kept going back and forth between what style I wanted to do. As an adult, I’ve done mostly watercolour work but in high school and college I was very into pen and ink. So I did quite a few watercolour sketches here and there but I hated the digital work that goes into cleaning them up for print. I’m lazy, let’s leave it at that. Pen and ink has less range of shading and of course it’s black and white, but it’s a little easier to digitize so I ended up with that after actual years of debating with myself. As far as actually producing the art, I’m really disorganized. As in, I use whatever paper I have (so later have to correct digitally), have my work tools spread out over every possible surface, draw standing up while waiting for things to cook; I’m just totally scattered. I find the hardest bit probably deciding what to illustrate from the story and then where to put that in the text. There’s was certainly stuff that didn’t make it in; cover ideas that hit the floor for sure. The other thing about black and white is that because you don’t have a lot of tone, pen and ink is helpful to this story because you can’t see the colours of the characters. In the book it’s noted that the world tries to convince you of differences while the important people around you try to convince you of your sameness. I want readers to be able to look at these characters and say Hey, what’s so different here? They all look the same to me.

There was a controversial “episode” in the book you almost didn’t include early on in the final manuscript that you decided to keep. What made you change your mind? “Controversial” is a subjective term, but I would say at first it struck me as too “adult-themed” to market to younger readers. Keep in mind when I began writing I was a kid and was writing to kids my own age and as the years went on I still kept that audience in mind. But when I sort of became aware I was writing a lot of my own life, it’s not that I didn’t want to write for small kids, I just felt the story had grown up with me and wasn’t on that level anymore. It was during my time really getting to know F’ala that this part of the book came up and like so much about her, figuring it out just clicked and made total sense. Now as far as keeping it in, I deliberately made it as vague as possible, not just for the sake of not exposing readers to that (I know many will know exactly what’s going on and will have had experience with this sort of thing; that’s just reality), but for the sake of protecting the character’s dignity. What is controversial within the story is that this is a very class-based society and even the fact that it happened at all changes how society slots a character into their class as well as what their rights and privileges are. While the same incident in our society in the real world garners a lot of questioning of the victim, in the book that’s not the focus. The characters of Ebūda take it as a matter of course that it happens in that particular area and it changes the class of a character, which is held as the most important social identifier. The thing is, only F’ala knows this is in her past and it erodes her self-worth throughout the rest of her life. So I kept it in because that bit of it goes on in our world constantly. The message with F’ala and keeping that in is that I hope readers take from it that victims aren’t stripped of their importance to the world because of what happened to them- F’ala is absolutely one of the most important characters in this book and arguably as important as Mi’hal’ē to the ending of the story.

What is the main thing you hope to accomplish in The Book of Moon? To let readers know they’re not alone. As I’ve mentioned, I read a lot as a kid and I really liked sort of fantasy-genre stuff that let me forget reality. But not until my mid-30s did I have that “OMGOSH!” moment in reading. I had been meaning to read the Austin Family books by Madeleine L’Engle for years and was off work for surgery, so I finally had the time to do so. I was reading The Moon By Night and just felt like for the first time in my life, someone got what it was like to be a teen for me, in my own life. I completely connected with the character of Vicky Austin and I was just stunned that the author, someone who had lived and been a teen and died by the time I read her book, just knew. And it was like, someone reached back to me in time when I was that age and said hey, it’s cool, I feel like that too. I would love for someone to pick up The Book of Moon and get that same feeling because when you know you’re not alone, you can do pretty much anything. That’s a strength like no other.

One final question: What is that red text on the back cover? Oh, it’s the Dala-ang translation of something in the book. Someone will figure it out, I’m sure.

photo by D. Chalich

© K.Rose Quayle 2019

Author photos by D. Chalich